The words “Participating Preferred” are perhaps the most feared, reviled and misunderstood words that can appear in a venture capital (or angel) term sheet. This post will not get into whether a company should accept some form of participating preferred, but will instead try to explain the term and hopefully eliminate some of the FUD around it (we’ll cover the cons/pros in a ‘mega-post’ on term sheets due out soon sometime).

Participating Preferred can be included as part of the structure (terms) of a Series of Preferred Stock. The objective of this term is to provide that Series of Preferred a better return in the case of an acquisition (or winding up of the Company) than it would receive from the total value of an acquisition based on its ownership percentage of the Company. We focus on acquisitions because it is rare for participating features to survive an IPO. With an IPO, Preferred Stock typically converts to Common prior to the offering and Preferred rights therefore go away (the notable exception is an IPO that does not meet minimum size or value thresholds outlined in a Preferred financing where Preferred holders do not agree to waive these minimums – this is rare).

Why does the concept of Participating Preferred Exist?

Simply put, the Participating Preferred structure exists to both limit the downside and enhance the upside on an investment. On the downside, Participating Preferred enables investors to receive their original investment amount back first, which means the total value of a Company at exit only has to be as much as the overall preference amounts for investors to break-even on the deal, whereas if this were tied strictly to ownership percentages it would take a much bigger outcome to break even on the investment. On the upside, a Participating Preferred structure allows an investor to get paid an amount greater than the value of their ownership percentage in a Company, so in scenarios where they recover their initial investment amount, they have the ability to generate a return greater than they would receive based solely on percentage ownership.

As stated above, we will not get into the merits and drawbacks for this term in the current article. There are reasonable arguments for and against using this feature that depend partly on which side of the table you are sitting on. For now, suffice to say it is one of the key terms in an investment term sheet, so you should understand it, and the impact it can have on your Company.

Three Types of Participating Preferred

There are three primary structures for Participating Preferred: (1) Non Participating, (2) Participating Preferred with no Cap, also known as Full Participating Preferred, and (3) Participating Preferred with a Cap.

Non-Participating Preferred – A Series of Preferred Stock that is non-participating will receive an amount equal to its percentage share of ownership in a Company (on an as-if converted to Common basis) in the case of an acquisition or winding up of the Company. In other words, if the particular Series of Preferred owns 40% of the Company on an “as if converted to Common” basis, it would receive 40% of the proceeds available to shareholders in the case of an acquisition. This proceeds amount is net of any other liquidation preferences in place, for instance for other Series of Preferred Stock in the Company.

Note: Explanation of “As if converted to Common” – When a new Series of Preferred is issued, it usually will convert into Common Stock on a 1:1 basis, meaning that for each share of Preferred Stock owned, the holder can exchange it for one share of Common Stock. This ratio can change over time, but usually will only change based on the triggering of “Anti-Dilution” provisions which will increase the number of shares of Common received for each share of Preferred converted. We will write a post on “Anti-Dilution Protection” soon and link to it from here when available, but for the purpose of this article we will assume everything converts on a 1:1 basis.

Full Participating Preferred – Also known as Participating Preferred with no Cap, this structure means that the Series of Preferred Stock it pertains to has a right to receive an amount equal to its “Original Purchase Price” plus its percentage ownership share of proceeds, no matter what multiple of invested capital it ultimately receives. So,whether the holders of this Series of Preferred receive a two times return on their investment or 50 times, they still receive a 1x preference amount in addition to their percentage ownership proceeds. We’ll opine only once in this post to say we believe Full Participating Preferred should go the way of the Dodo bird, but again, will leave the details behind that opinion for another post.

“Original Purchase Price” Explained – For a single share of Preferred Stock, “Original Purchase Price” is the amount paid to purchase that share, sometimes referred to as the Series price. For the entire Series of Preferred Stock it is the cumulative amount paid to purchase all of the shares of that Series. Participating Preferred typically receives this amount plus “any declared but unpaid dividends”. For the purposes of this article we ignore the dividends piece because it is incredibly rare for a venture-backed company to declare dividends while it is still a private company. The “Original” component of this is important in that if the shares are sold in a secondary sale to another purchaser, the amount paid in that secondary transaction does not impact the amount paid for liquidation preferences – the new holder is only entitled to preferences for the “Original” price paid by the first purchaser of these shares.

Participating Preferred with a Cap – The “Cap” feature sets a limit on the multiple of return on invested capital that a series of Preferred Stock can receive before its participation feature is cancelled. For instance, if the Cap is set at two times (2x) invested capital, the Series holders would participate up until they receive two times the “Original Purchase Price” of that Series, after which they would not receive any further proceeds from the acquisition. However, holders of this Series of Preferred have the option to convert their Preferred Stock to Common Stock ahead of the close of the transaction if they decide they are better off converting to Common Stock, in other words, if they would receive a greater than 2x return multiple on their invested capital if they convert to Common Stock and give up their Participating Preferred rights. This is important to note as we know some people mistakenly believe the Cap feature is a fixed cap for the total return a Series of Preferred Stock can receive no matter what the overall outcome. This is not the case, and these holders are not limited to the Cap if their ownership percentage of the Company would result in a return that is greater than the Cap amount.

The purpose of the Cap is to set a return threshold above which the additional proceeds received from the participating feature disappear. The reasoning behind this is that if the overall return to an investor is above some multiple of invested capital they should no longer receive proceeds that exceed their actual percentage ownership in the business.

What is the difference between “Liquidation Preference” and “Participating Preferred”?

It is important to note that “Liquidation Preferences” are very much related to “Participating Preferred” in that the latter is a structural instantiation of the former. However, “Liquidation Preferences” cover a broader range of terms than “Participating Preferred”. Generally speaking, liquidation preference terms define which Series of Stock gets paid first, what amount it is paid, and the specific circumstances that determine these payouts (the amount and circumstances being defined by as the Participating Preferred structure). Liquidation Preferences and the structure of Participating Preferred will be outlined in the term sheet provided by a prospective investor, although it is likely that the phrase “Participating Preferred” will not appear in the document. For the closing documents of the financing, the details for these terms will be included in the Amended and Restated Articles of Incorporation.

Liquidation Preferences and Participating Preferred in Venture Financing Documents

Below is the actual language related to Liquidation Preferences for a Series C term sheet received by a Company. In this case you will see that the Series C has a liquidation preference ahead of other Series of Preferred Stock and Common stock, and that there is a 2x Cap on the preference (Participating Preferred with a 2x Cap). In this situation, each Series of Preferred has a liquidation preference that allows it to recover the its “Original Purchase Price” ahead of the Series of Preferred Stock that preceded it and ahead of Common Stock. In other words, the Series C gets repaid, then the Series B, then the Series A, and then all these Series participate with Common Stock in the remaining proceeds at their respective percentage ownerships (on an “as if converted to Common” basis) until each Series of Preferred Stock has received a total of two times its Original Purchase Price. When this language is spelled out in greater detail in the closing documents, it will take up (in this specific case) over two pages, but the key details are all encompassed in the term sheet paragraphs below:

Liquidation Preference: In the event of any liquidation or winding up of the Company, the holders of Series C Preferred will be entitled to receive in preference to the holders of Common, Series A Preferred and Series B Preferred, an amount equal to the Original Purchase Price plus any dividends declared on the Series C Preferred but not paid (the “Series C Liquidation Preference”). Thereafter, the holders of Series B Preferred will be entitled to receive in preference to the holders of Common, and Series A Preferred, an amount equal to the Series B Preferred original purchase price plus any dividends declared on the Series B Preferred but not paid (the “Series B Original Purchase Price”). Thereafter, the holders Series A Preferred will be entitled to receive in preference to the holders of Common an amount equal to the Series A Preferred original purchase price plus any dividends declared on the Series A Preferred but not paid (the “Series A Original Purchase Price”). Thereafter, the holders of the Series A Preferred, Series B Preferred, and Series C Preferred shall participate with the holders of Common on an as-converted basis until the holders of Series A Preferred, Series B Preferred, and Series C Preferred each receive an aggregate of two times (2x) the Series C Original Purchase Price, the Series B Original Purchase Price and the Series A Original Purchase Price, respectively (including amounts paid pursuant to the immediately preceding two sentences). Thereafter, the holders of Common shall be entitled to receive all remaining assets.

A consolidation or merger of the Company following which holders of the Company’s outstanding stock immediately prior to such event own less than 51% of the voting stock of the surviving entity or its parent, or a sale of all or substantially all of the Company’s assets or stock, other than in connection with an equity financing for cash, shall be deemed to be a liquidation or winding up for purposes of the liquidation preference.

The Participating Preferred “Dead Zone”

Including a Cap in the terms of Participating Preferred stock introduces a phenomenon we term the “Dead Zone”. The preferential payment from Participating Preferred Stock will result in a Series of Preferred reaching any multiple of its “Original Purchase Price” at a lower overall exit value than it will reach that same multiple based on ownership percentages alone. If a Cap is put in place that limits the multiple the Series can get and still retain a preference feature, there will be a Dead Zone between the exit value that results in the Series of Preferred reaching this Cap with the payment in place (the “lower bound”), and the exit value required for this Series of Preferred to reach the same return multiple based on percentage ownership alone (the “upper bound”). The range between these two exit values is the “Dead Zone”. It is the range of exit values for the Company between which a specific Series of Preferred will receive no additional proceeds, and as a result is financially indifferent between an outcome at the bottom or top of this range. Once the upper bound value is reached, the Series of Preferred would be better off converting to Common Stock because the proceeds received based solely on ownership percentage will produce a return multiple greater than the Cap level. To repeat, the Preferred would not want to convert to Common Stock until the exit value of the transaction reaches the upper bound of the Dead Zone. The Dead Zone phenomenon is illustrated in the examples below.

If there are multiple Series of Preferred Stock with Liquidation Preferences, the Dead Zone will be different for each Series of Preferred. The range for each depends on multiple factors including Original Purchase Price per share, preference seniority, anti-dilution protection effects and the preference cap (if any) for each Series. As a result, there will be multiple, sometimes overlapping Dead Zones.

Note: The Dead Zone phenomenon does not occur with Full Participating Preferred because in this structure the Series of Preferred receives the preferential payment amount no matter what the outcome and regardless of the overall return multiple.

Factors Impacting a Decision to Convert or not Convert Participating Preferred with a Cap

The decision on whether or not to convert Participating Preferred with a Cap is usually a simple one. If the exit value would not come close to reaching the Cap multiple, an investor would not convert. Conversely, if the exit value is large enough that the return multiple based on percentage ownership is well above the Cap level, an investor will convert to Common. Situations sometimes arise when the return is close enough to the Cap level (near the upper bound of the Dead Zone) that a number of factors may come into play that will make the decision about converting to Common an imperfect one.

The three most common situations that can make it difficult for an investor to decide whether or not to convert to Common Stock and give up the preferential payment are Escrows, Earn-Outs and certain transactions where the purchase price is paid in Stock. Without going into these in detail, suffice to say there will be times when the conversion decision is a difficult and imperfect one, and can result in a meaningful degree of angst in negotiating and finalizing an M&A transaction. The easiest way to avoid this is to have a crushingly huge success that blows through the Cap levels, so just plan on doing that, ok?

Participating Preferred Examples

The examples below will illustrate the impact of and differences between the three types of Participating Preferred described above. For the sake of simplicity we will focus on a company that has only two Series of stock, Common Stock and Series A Preferred. We’ll cover a few more complex situations in a follow-up post (multiple Series of Preferred, pari passu vs senior preferences and down rounds).

For the following examples, we will use a scenario where a start-up has raised $4 million in Series A financing at a $6 million pre-money valuation. We’ll assume the Series A was priced at $1.00 per share and there are a total of 10 million shares outstanding (Common and Series A combined). To simplify matters further, we’ll assume there are no stock options, just Common Stock. Given this structure, the cap table for the Company will look like this:

Now lets assume the Company gets acquired (hurray!). After paying lawyers, bankers, accountants and ambulance chasers, we’ll assume net proceeds available to the equity holders in the Company are $22 million.

Example #1: Non-Participating Preferred

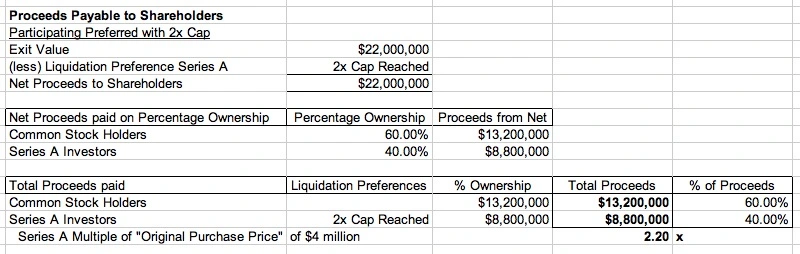

If there are no participation rights for Preferred, the $22 million in available proceeds would be shared amongst the stockholders based on their ownership percentages. In our simple cap table, the Common Stock Owners would get 60%, or $13.2 million, and the Series A Investors would get the other 40%, or $8.8 million. This outcome is depicted below:

This snapshot shows the Exit Value of $22 million, which because there are no participation features is also the amount of Net Proceeds to Shareholders. This amount is divided between Common and Series A based on their ownership percentages. The final section shows the proceeds to Common and Series A from Liquidation Preferences and % Ownership. In this case it all comes from ownership since there are no liquidation preferences. This section of the table also calculates the percentage of total proceeds received by Common and Series A, and shows the return multiple of the original $4 million purchase price for Series A, in this case a 2.2x return.

Example #2: Full Participating Preferred

Let’s next move to the simplest form of Participating Preferred to model – Full Participating Preferred (no Cap).

Without any other qualifiers, this phrase is essentially the same as saying “one x” (or “one times”) Participating Preferred”. If no “Cap” is mentioned, there is not one in place, so this Preferred Stock will receive a preferential payment equal to one times its “Original Purchase Price” regardless of the overall value of the transaction (unless of course the sale price is so low that there are not enough proceeds to cover this preferential amount, in which case the available proceeds would be shared between the Series A holders on a “pari passu” basis).

Full Participating Preferred. The Series A investors will get a preferential payment equal to one times the “Original Purchase Price” of the Series A round. After this amount is paid, the remainder of the proceeds available to shareholders from the sale of the business will be split up based on equity ownership of the Company, with the Series A being treated as though it was converted to Common Stock (recall we are assuming a 1:1 Preferred Stock to Common Stock conversion ratio in all examples).

Lets look at the impact of the Participating Preferred feature where it is set as Full Participating Preferred. We’ll depict it in spreadsheet form and then describe it in text:

From the $22 million in proceeds available to equity holders, the preference paid to Series A shareholders of $4 million (equal to the “Original Purchase Price”) is deducted from the total proceeds. This leaves $18 million in net proceeds still available. This $18 million is paid out based on ownership percentages, so the Common Stock receives 60%, or $10.8 million, and the Series A Preferred receives 40%, or $7.2 million (remember that in this example a share of Series A is treated like a share of Common when determining how the remaining proceeds from the sale of the business are paid out). Adding the $4 million in liquidation preferences to the Series A proceeds, the holders of Series A Preferred will receive $11.2 million of the $22 million total, and Common holders will receive $10.8 million.

In looking at the impact of Full Participating Preferred, we see that instead of getting $8.8 million (40%) of the $22 million in proceeds, the Series A received $11.2 million, or 51%, while the Common Stock received $10.8 million, or 49% of the total (compared to its 60% ownership position). The multiple of return for Series A increased from 2.2x ($8.8 million proceeds divided by $4 million invested) to 2.8x. This .6x preferential return will remain no matter what the total value of the outcome is, $22 million as in this example, $220 million or $2.2 billion.

It is worth noting that the “cost” of Participating Preferred is shared equally by all shareholders since the amount of proceeds available to pay based on ownership percentages is reduced. As such, while the Series A in this case had a 1x preference with no Cap, its overall benefit from this 1x preference was equal to an additional return of .6x (not 1x). This ratio is based on the amount owned by the Preferred Series with the Participating Preferred feature – the benefit to that Series will be equal to the 1x preference less the percentage ownership that Series holds in the Company. In this example the Series A owns 40%, so the benefit is 1x minus .40 (40%) or .6x. Note – this calculation only works when there a single Series of Preferred and no Cap in place – adding a Cap starts to make things “interesting” in terms of exit calculations.

Example #3: Participating Preferred with a Cap)

Finally we’ll cover the Participating Preferred with a Cap. We left this for last because it is the most difficult to model (and explain). The reason for this is that the calculations used to determine the amounts paid to Common and Series A will change based on the total value of the transaction. More specifically, the way these proceeds are calculated will change when the Series A reaches the Cap limit, and then will change again when it would be better for the Series A to convert to Common Stock which occurs when the Series A would receive a return of more than the Cap limit based solely on ownership percentage.

For this example we will assume there is a 2x Cap on the Participating Preferred. Using the same ownership and investment scenario as above, we can easily calculate the exit value required for the Series A to receive a 2x return with the participating payment in place. The first 1x return (the $4 million initially invested) for Series A comes off the top (this is commonly referred to as the “liquidation preference” or “preference amount”), so at a $4 million exit value, the Series A will get back its entire investment while Common receives nothing.

After the first $4 million, the Series A Preferred and Common Stock will receive their respective ownership percentage of every additional dollar of exit value up until the Series A has received an additional $4 million (another 1x of invested capital), which gets the Series A to a total return of 2x, meaning it has reached the Cap. In our example, the Series A owns 40% of the Company, so the math to figure out the total exit value required to hit this level is pretty easy. With an additional $10 million in exit value, 40%, or $4 million will go to Series A, while the other $6 million goes to Common. So, at a total exit value of $14 million, Series A has reached its 2x Cap. At this Series A receives $8 million (57.14% of total proceeds) while Common Stockholders receive $6 million (42.86% of total proceeds). In this example, the $14 million exit value is the lower bound of the “Dead Zone”.

For any exit value greater than $14 million, the 2x Cap has been reached. From this point forward, the Series A holders can elect to keep the preference payment in place and stick with a total return of 2x, meaning that all additional proceeds go to Common Stock only, or the Series A can elect to forgo its preference by converting to Common Stock.

Now let’s look at the $22 million exit scenario we used in the prior two examples. Remember that the 2x Cap has been hit, so the Series A can either stick with the preferences, or convert to Common Stock. Before looking at the table below, try to do the calculations necessary to determine which decision is better for the Series A holders – should they take a 2x total return on their $4 million investment with the preference payment, or give up the preference and get their ownership percentage (40%) of the $22 million transaction?

Here is the answer:

At the $22 million acquisition price, if the Series A were to take its preference payment and stick to a 2x Cap on total return it would receive $8 million in proceeds. By converting to Common Stock, the Series A holders receive 40% of the exit value, or $8.8 million in proceeds (a 2.2x return). So, at a $22 million exit value, the Series A would plan to convert to Common.

So, what is the upper bound of the Dead Zone, the exit value at which the Series A would first decide to convert to Common Stock and forgo the preference payment? The simple way to calculate this is to determine the exit value at which the Series A would receive the same return multiple based solely on ownership percentage as it would with the Cap in place, in this case 2x. Since a 2x return for the Series A is $8 million, you can divide this amount by the ownership percentage for Series A (40%) to determine the exit value above which a conversion to Common would make sense. In this case the answer is $20 million. This is the upper bound of the Dead Zone. The Series A will not want to convert to Common Stock until the exit value has passed the upper bound of the Dead Zone.

The “Dead Zone” Illustrated

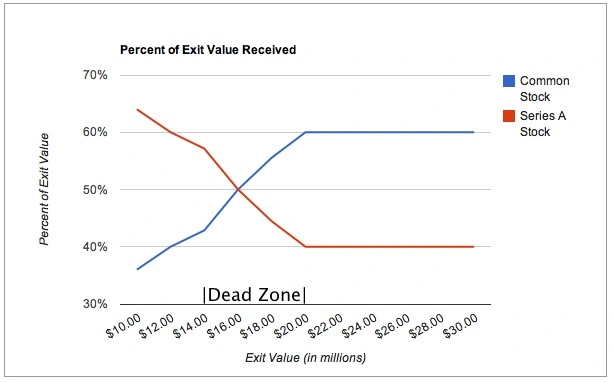

Using the example above, the “Dead Zone” had a lower bound of $14 million and an upper bound of $20 million. The return multiple to Series A investors hit the 2x return cap with the preference payment at a $14 million exit, and it would require a $20 million exit value to provide this same 2x return based purely on ownership percentages. The entire exit value of the transaction within the Dead Zone, from $14 to $20 million, will go to Common Stock. In the process, the share of proceeds to Common will increase from 42.86% up to the Common Stock ownership percentage of 60%. For exit values above the Dead Zone, the Common Stock will continue to receive 60% of the proceeds.

The two charts below illustrate both the Dead Zone and the impact of Participating Preferred with a Cap. The first chart shows the proceeds paid to Common Stock and Series A Stock as the Exit Value increases from $10 million to $30 million. Note that within the Dead Zone from $14 to $20 million, the red line (Series A) stays flat as no additional proceeds are received. At a $20 million exit value, Series A would convert to Common Stock and start to receive its share of proceeds based on ownership (40%). From this point forward the blue and red lines will diverge as 60% of proceeds go to Common Stock and 40% to Series A.

The second chart shows the same data on a “Percent of Exit Value Received” basis. You can see that at a $10 million exit, Series A receives over 60% of total proceeds while Common Stock receives less than 40%. As the Exit Value increases, Common Stock receives a greater percentage of the total value. This accelerates in the Dead Zone unitl it hits the Common Stock ownership percentage of 60% at the upper bound of the Dead Zone, after which the line stays flat for all higher exit values while the Series A settles in at its 40% ownership level.

The two charts go a great job of showing the impact of Participating Preferred in terms of how the proceeds are split when compared to straight equity ownership. You can see that the impact of Participating Preferred is more significant at lower exit values and as the total exit value increases, the relative share of exit proceeds moves towards equity ownership splits. Seeing the Dead Zone illustrated should make you wonder why the Series A would care if the final exit value was $14 million versus $20 million as they do not get any more from the deal and pushing for the last million(s) can be risky. We’ll cover this and other potential issues to keep in mind in an opinion piece sometime soon.

More Complex Preference Situations

Seriously, you want to go into this? You are not up to your eyeballs in Participating Preferred at this point? We are.

Ugh. Ok, we’ll continue this in a second post, but if you have read this far we hope you’ll at least give us a shout out on Twitter or “Like” us somewhere out in the ether. Links to this post would also be most appreciated as we spent a LOT of time putting it together and would like to see it help as many people as possible understand these concepts.